EXHIBITIONS

We are preparing for the next exhibition.

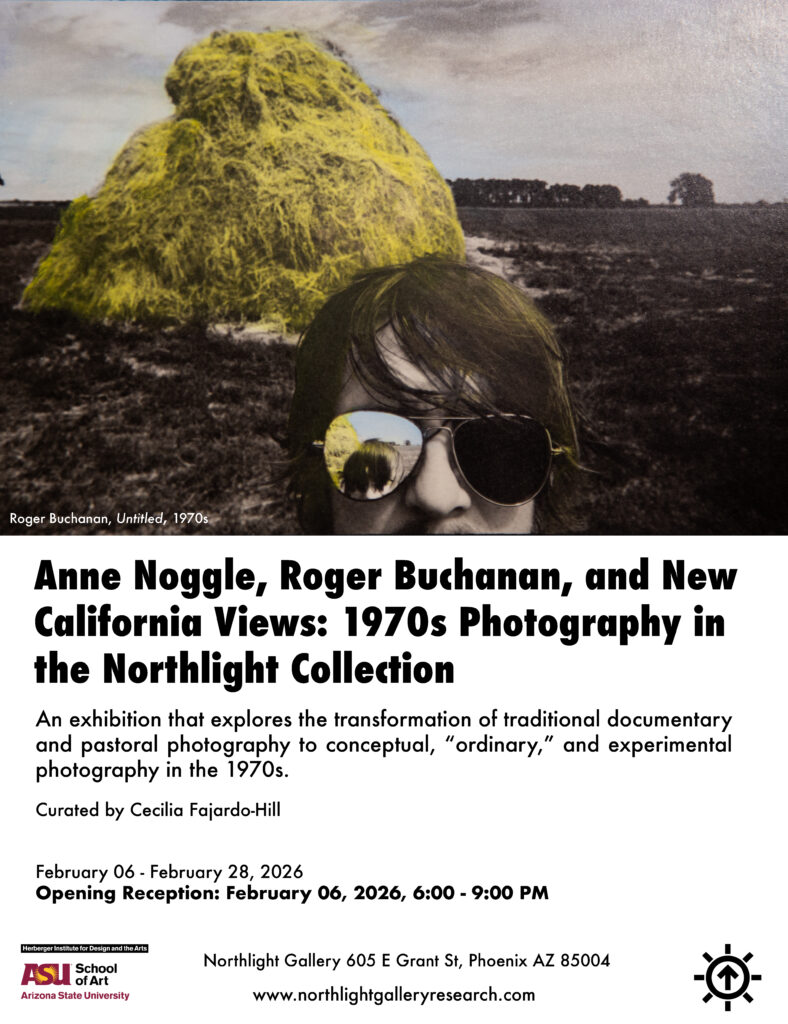

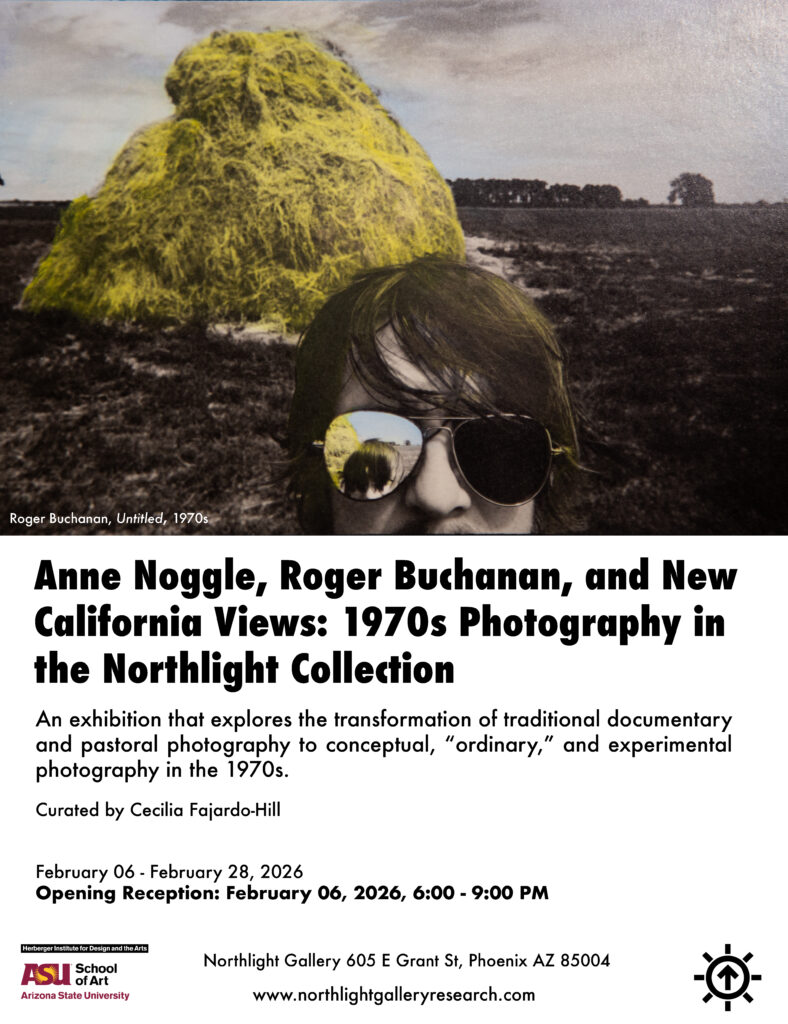

Anne Noggle, Roger Buchanan, and New California Views: 1970s Photography in the Northlight Collection

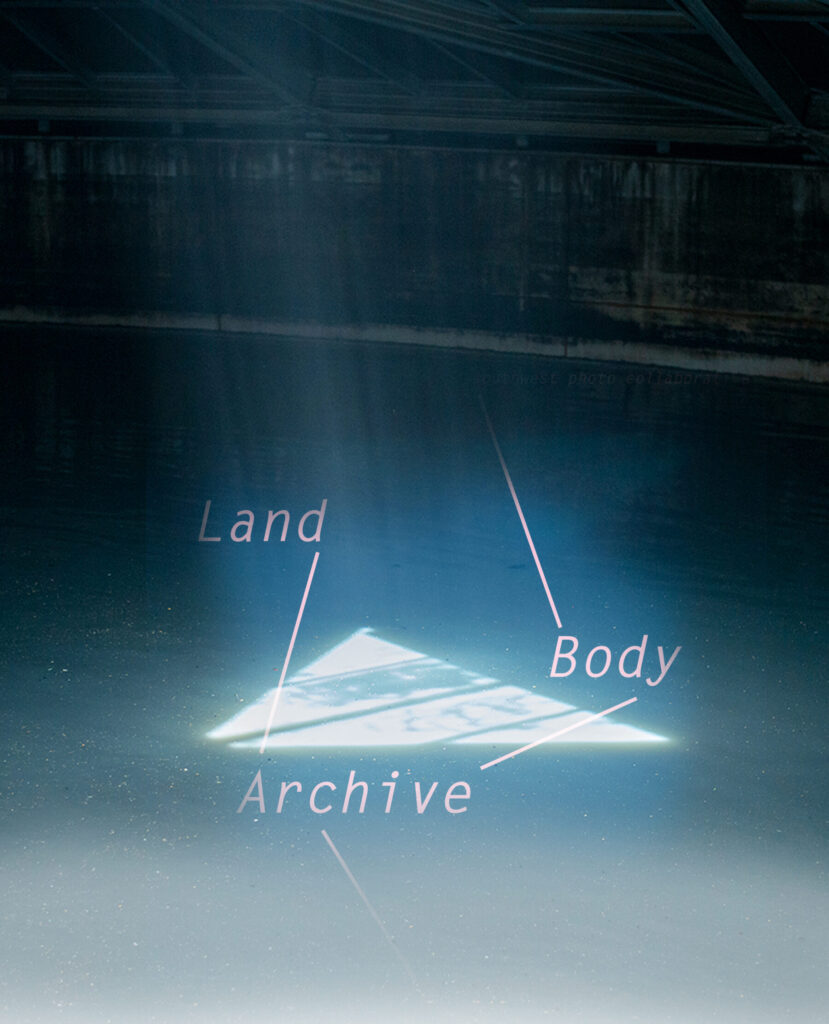

The 1970s was a decade marked by change, economic and energy crises, the Watergate scandal, the continuation of the civil rights movement, protests against the Vietnam war, economic inequality, activism for lgbtqia and women’s rights, and affirmative action. Photography during this period was transformative, as it shifted from traditional documentary and timelessness to conceptual, “ordinary”, and experimental–questioning the presumed objectivity and truthfulness of photography. The 1970s gave way to the rise of color photography, snapshot aesthetics, and raw documentary photography of mundane, suburban everyday life. 1970s photography encompassed critical and ironical representations of contemporary American culture and consumerism, as well as socially critical and political photography.

The New California Views portfolio, 1979 embodies the shift from traditional romanticized landscape photography to the changing landscape, particularly in the American West, with the expansion of suburbia around urban centers like Los Angeles. The photographers in this portfolio focus on the industrialization of the environment and the concept of the suburban and contemporary landscape. Many photographers in the 1970s turned their cameras on themselves and close family members, informed by second-wave feminism and gender and social activism, creating what has been described as “Intimate Documentary.”, exemplified by Anne Noggle (1922 – 2005), as she photographed herself and other women, documenting mutual aging processes, which she described as “the saga of the fallen flesh.” Beyond the documentary, Noggle’s photographs possess a sense of humor, directness, and agency, not shying away from representational taboos related to the aging body, particularly of women, such as nudity and plastic surgery. Roger Buchanan (1940 – 2024), an Arizona based photographer and alumni from the ASU Photography Program, was an experimental photographer as well as photojournalist and advertising photographer. In the context of the 1970s rise of photo experimentation, Buchanan is a key example as he created bizarre and often loaded photocollages and photomontages by combining different photographic techniques such as printing multiple negatives, solarization, hand color-tinting, and collaging found objects onto the surface of the works. His subjects were animals such as dogs and ducks, as well as himself, nude women, and other individuals set on dilapidated or strange backdrops.

The Northlight Gallery was founded in 1972 and hosts a collection of over 3000 photographs that tell the stories not only of ASU’s Photography Program, but the history of fifty years of photography in the United States. This selection demonstrates the curatorial and academic potential of this transformative collection by focusing on a group of important regional artists that embody the ethos and impactful changes of photography in the 1970s.

Cecilia Fajardo-Hill

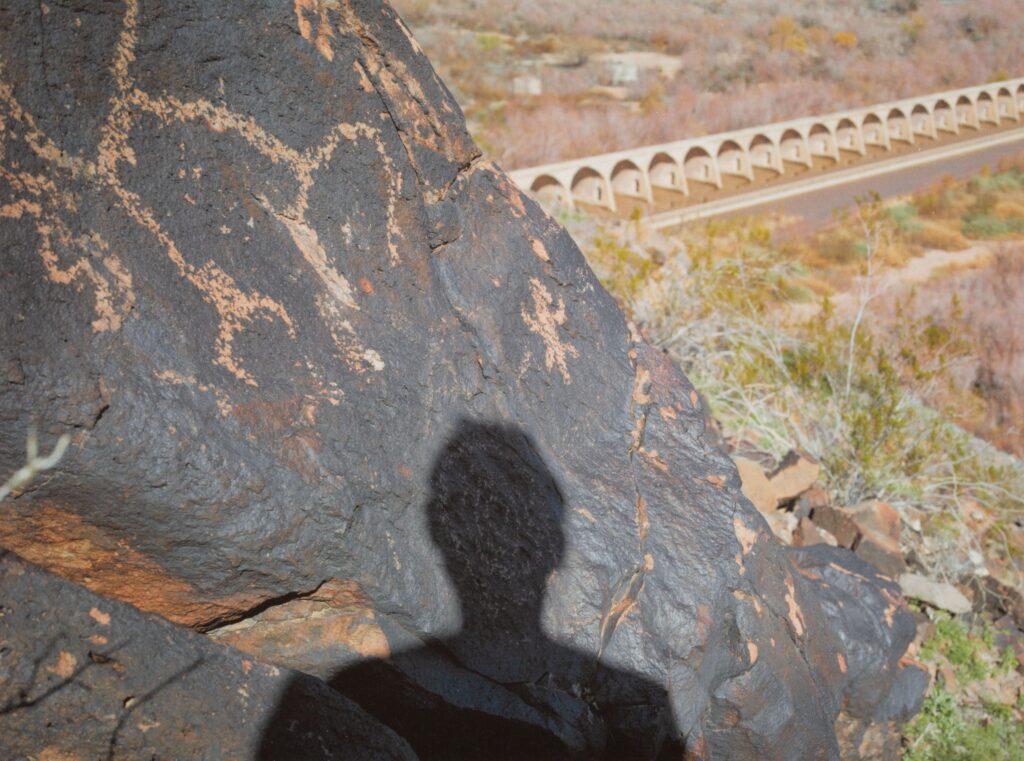

New California Views, 1979

In the New California Views portfolio, 1979 producer Victor Landweber states, “This collection of photographs moves away from traditional landscape photography by artists such as Muybridge, Ansel Adams, and Weston, to align broadly with the shift in the medium and the 1970s towards a more conceptual, critical and direct photography”. While some of the photographs in the portfolio are presented in dialogue with an earlier tradition of landscape photography of the American West, often characterized by idealized views of wilderness and the promotion of settlement and development alongside subjects such as the railway; the landscape in the New California Views portfolio is subject to urbanization, where nature is no longer magnificent but uninspiringly suburban or absent entirely. As John Upton describes it, the portfolio is characterized by an“…absence of images intended to evoke nature as sublime and transcendent. …The concern represented here is that of images of cultural artifacts in the context of landscape, or of photographs which refer to the idea of landscape, rather than to an intrinsic image of the land.”

Approximately half of the artists in the New California Views portfolio lived and worked in Northern California. Their images are broadly rooted in the region’s photographic tradition: Jerry Burchard, Linda Connor, Steve Fitch, Wanda Hammerbeck, Roger Minnick, Richard Misrach, Arthur Ollman, Catherine Wagner, Jack Welpott, and Henry Wessel Jr. Photographers working in Southern California round out the portfolio with direct photography in dialogue with contemporary art of the time: Robert Cumming, Joe Deal, John Divola, Graham Howe, Victor Landweber, Kenneth McGowan, Sherrie Scheer, Stephen Shore, Arthur Taussig, and Garry Winogrand. Reflecting on the 1970s while examining this group of photographers, recognizes many as transformative to this period of American photographic history. We may highlight Stephen Shore, who is associated with the Düsseldorf School of Photograph, founded by Bernd and Hilla Becher, characterized by a form of conceptual serialized photography which tests the gap between documentary and artistic photography and Linda Connor, Robert Cumming, John Divola, Richard Misrach, Arthur Ollman, Henry Wessel, Jr., and Garry Winogrand, all of whom were included in the seminal “Mirrors and Windows,” at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1978. In a recent review of photography of the 1970s, curated by Andread Nelson, The ‘70s Lens: Reimagining Documentary Photography,at the National Gallery in Washington, 2024, was formulated to explore different themes that included key pioneers of the era, including some of the photographers represented within New California Views, such as Joe Deal in “Alternative Landscapes,” Robert Cumming under “Conceptual Documents,” Garry Winogrand in “Experimental Forms,” and Richard Misrach’s “Life in Color.” New California Views can also be found in the photographic collections of the Princeton University Art Museum, Harvard Art Museum, The Met Collection, Portland Art Museum, and The Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

Anne Noggle: “The Saga of the Fallen Flesh”

“I’m trying to humanize the middle-aged and older, to find a new perspective that … [lets] them be a viable part of society. I cannot view life as a tragedy alone.”

Anne Noggle (1922, Evanston, Illinois – 2005, Albuquerque, New Mexico) was an extraordinary photographer that led an exceptional life. She was a pilot and photographic pioneer beginning her artistic career at the age of 43 and becoming known for photographs that confront aging in self-portraits as well as personal portraits of older women such as her mother and other pioneering female combat pilots.

Her trajectory as a pilot speaks of Noggle’s indomitable spirit. Inspired by aviator Amelia Earhart, Noggle learned to fly at the age of 17 years old. In 1943 she volunteered as a Woman Airforce Service Pilot (WASP), graduating with the class of ‘44 to become part of an elite group of women flyers that towed target banners for air-to-air gunnery practice, ferried cargo planes, and served as flight instructors to male pilots. After the WASPs deactivated in December 1944, Noggle flew as a crop duster, a stunt pilot in an aerial circus, and later served as a Captain for the Air Force during the Korean War (1953-59). Following her aviation career, she obtained a BFA in 1966 and an MFA in 1969 from the University of New Mexico, where she taught from 1970 to 1996. Noggle had her first solo show at the age of 48. From 1970-1976 she was the curator of photography at the New Mexico Museum of Art and in 1975 co-curated the seminal exhibition Women of Photography: An Historical Survey, at the San Francisco Museum of Art, which introduced the work of many American women photographers to a broader audience. She was awarded a Guggenheim fellowship in 1992.

As a photographer Noggle gave herself and her aging subjects agency while exposing the imperfections and effects of physical decline such as wrinkles, unidealized bodies, or false teeth. She portrayed herself and her subjects’ aging process with candor, with a humanizing and respectful lens, as well as humor. Importantly she aimed to empower and make visible the unseen and marginalized aging woman as a subject. Charles Hagen wrote in a 1991 review for the New York Times: “The profound dignity in the women’s faces, as well as the admiration and affection with which Ms. Noggle depicts them, is tempered by the sharp sense of physical loss the pictures express”–highlighting the affective and involved nature of Noggle’s work. She referred to her self-portraits as “The Saga of the Fallen Flesh” and perhaps no image embodies this idea better than Face-lift No. 3, 1975, an unflattering self-portrait of Noggle after plastic surgery when she was 53, revealing unconcealed stitches, a puffy face and blackened eyes, while incongruously holding a flower in her lips. No other photographer has focused more poignantly on documenting the beauty, humanity and power of aging.

Roger Buchanan: 1970s Experimental Photography

Roger Buchanan (1940, Iowa – 2024, Payson, Arizona) was an Arizona based photographer, who received a BFA in 1971 and an MFA in 1973 from the Photography Program at Arizona State University. Buchanan’s teaching certificate was awarded in 1985 and he was an instructor in the Arts department at ASU and Phoenix Community College. An ex-marine and ex-nursery man, while still a student at ASU, he happened to be a passenger on the Trans World Airlines Flight 486 between Phoenix and Washington, when it was hijacked by an unemployed truck driver, Arthur Barkley, on May 7, 1970. Buchanan garnered national attention by riskily photographing the hijacker and other passengers during the event. The 1970s was a period of immense experimentation and photographic activity for the artist. Buchannan became a quintessential photojournalist, both locally and nationally, covering sports such as rodeo, lacrosse, skiing, boxing, horse trade, chess, news, homicides investigations, creative fashion, as well as community events and individuals. At times he also wrote the articles he illustrated, covering unconventional topics such as the black widow spider, and also collaborated with his mother Marguerite Noble (Buchanan) a well-known historian of Arizona History with photographs for her articles. While Buchanan was still studying at ASU, his documentary, photojournalistic and artistic work had already been published in magazines such as Life (1970), Modern Photography (1973, 1974), Camera 35 (1972), New York Times Magazine (1972), and Paris Match.

To finance his experimental artistic photography, he covered rodeos, weddings, and worked in advertising photography. Nevertheless, Buchanan’s photojournalistic or advertising photography was often eccentric and unconventional, creating composite images, and strange super- and juxta-positions. He was quoted in 1970, declaring: “I’ll take a cliche shot of a model, and in order to keep it from being a cliché I may tell her to grab a bucket and hold it up her head.”

In 1974, Buchanan was awarded a National Endowment for the Arts Grant and was asked to photograph the activities at the Artists-In Schools Program (AIS) at St. John’s Indian School on the Gila River Reservation (akimel o’odham/piipash). His documentation grew into “Seeds of Gila: A Visual Exploration of the Pima Condition in the Shadow of the Sacred Mountain” which was presented at the Phoenix Art Museum in 1975 and the Arizona State Capitol.

It is surprising that despite the broad local and national exposure of Buchanan’s work over the decades, his work has receded into near oblivion. The works exhibited at Northlight in 2026 were recently generously donated by his daughter, Laine Munir, who is an Assistant Teaching Professor at the School of Politics and Global Studies at Arizona State University. This exhibition is a first attempt at reappraising the extraordinary body of work of a remarkable artist.

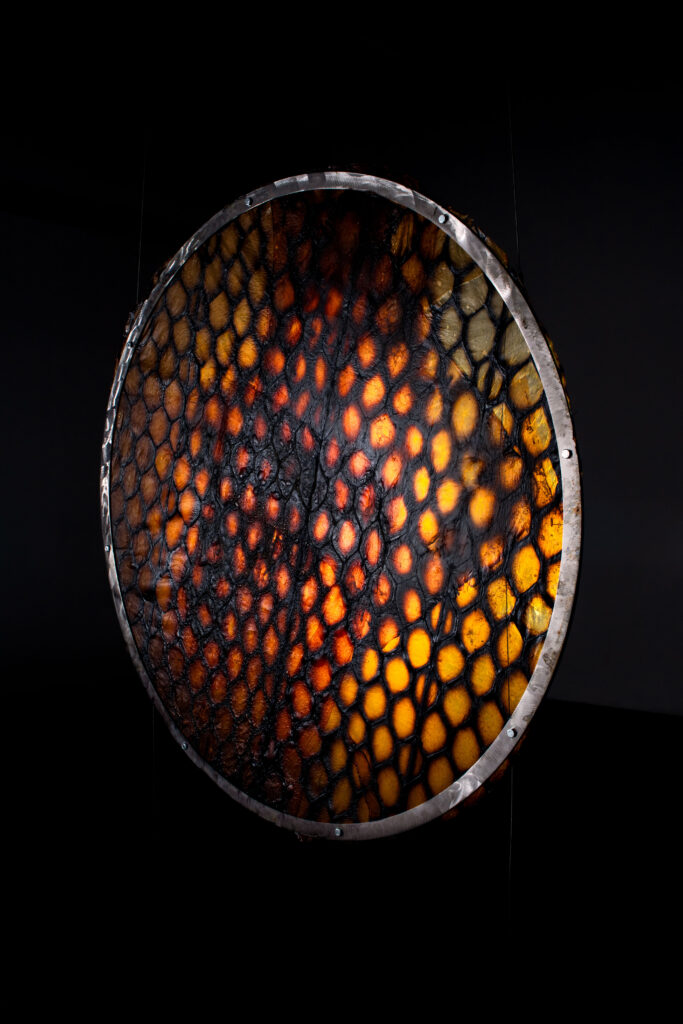

Roger Buchanan Experimental Photography

In his “surreal” photocollages and photomontages from the 1970s, Buchanan used several photographic techniques to achieve the final works, such as printing two or more negatives, solarization, bleaching, pasting photograph over photograph, combining black and white and color photographs, hand color-tinting, and collaging objects onto the surface of the image to create sculptural and tridimensional effects. Buchanan also created hybrid pieces between furniture and sculpture, made with found materials such as driftwood and various local woods, barn wood, found objects from farms, such as rusted metal, old glass, animal bones, feathers, and natural stones from ranches and abandoned sites. Some of these pieces and individual elements were used as backdrops and components of his staged photographs. He also owned turkeys, chickens, and other animals that appeared in some of his works. Of special mention is Agate, a dog with heterochromia with one-white-eye and one-brown-eye, who appeared in many of his photographs. Himself, nude women and other subjects were also often integrated in his compositions and placed in strange settings or against bizarre backdrops.

To describe the experimental process Buchanan used to create his photomontages, an article in Nikon World, describes Untitled, c. 1970s, as the artist’ attempt to picture his demise, creating a fantasy with several negatives. The “sky” is from a shot of the ocean, the sheep were photographed on the Navajo Nation, and the artist posed for the picture while lying on a beach in Baja, Mexico. Buchanan sandwiched the negative with a close-up of toadstools. For the final printing three enlargers were used to create three separate negatives: the sky (ocean), the sheep, and the artist and toadstool sandwiched. For the final print the face was bleached to simulate death, hand tinting applied, and the print trimmed in a shape to resemble an icon. Some of these experimental works from the 1970s were shown at the Third Arizona Photography Biennial held at the Phoenix Art Museum in 1971, and the Tenth Southwestern Invitational at Yuma n.d. circa early 1970s.